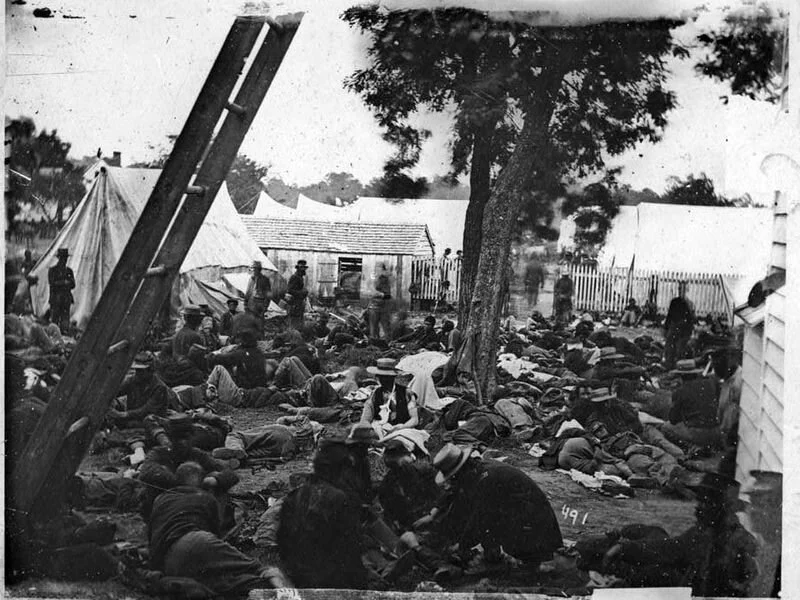

A field hospital in Virginia, photographed in 1862, shows the grim conditions during the Civil War. (Library of Congress; Photo by James Gibson)

People knew that inoculation could prevent you from catching smallpox. It was how Civil War soldiers did it that caused problems

By Kat Eschner

SMITHSONIANMAG.COM

MAY 1, 2017

At the battle of Chancellorsville, fought this week in 1862, nearly 5,000 Confederate troops were unable to take their posts as the result of trying to protect themselves from smallpox.

And it wasn’t just the South. “Although they fought on opposite sides of the trenches, the Union and Confederate forces shared a common enemy: smallpox,” writes Carole Emberton for The New York Times.

Smallpox may not have been as virulent as measles, Emberton writes, but over the course of the war it killed almost forty per cent of the Union soldiers who contracted it, while measles—which many more soldiers caught—killed far fewer of its sufferers.

There was one defense against the illness: inoculation. Doctors from both sides, relying on existing medical knowledge, tried to find healthy children to inoculate, which at the time meant taking a small amount of pus from a sick person and injecting it into the well person.

The inoculated children would suffer a mild case of smallpox—as had the children of the Princess of Wales in the 1722 case that popularized inoculation—and thereafter be immune to smallpox. Then, their scabs would be used to produce what doctors called a “pure vaccine,” uninfected by blood-borne ailments like syphilis and gangrene that commonly affected soldiers.

But there was never enough for everyone. Fearing the “speckled monster,” Emberton writes, soldiers would try to use the pus and scabs of their sick comrades to self-inoculate. The method of delivery was grisly, writes Mariana Zapata for Slate. "With the doctor too busy or completely absent, soldiers resulted to performing vaccination with whatever they had at hand. Using pocket knives, clothespins and even rusty nails... they would cut themselves to make a deep wound, usually in the arm. They would then puncture their fellow soldier's pustule and coat their wound with the overflowing lymph."

The risk of getting smallpox was bigger to the soldiers than the risk of bad infections from this treatment. But besides the lack of sanitation, the big problem was that their comrades might well have other had other ailments or even not had smallpox at all. “The resulting infections incapacitated thousands of soldiers for weeks and sometimes months,” Emberton writes.

Smallpox was just one note in a symphony of terrifying diseases that killed more Civil War soldiers than bullets, cannon balls and bayonets ever did. Although estimates vary on the number of soldiers who died during the war, even the most recent holds that about two of every three men who died were slain by disease.

That’s not hard to understand, given the conditions of the camps and the fact that the idea of doctors washing their hands hadn’t reached North America yet. There’s a reason that the Civil War period is often referred to as a medical Middle Ages.

“Medicine in the United States was woefully behind Europe,” writes the Ohio State University department of history. “Harvard Medical School did not even own a single stethoscope or microscope until after the war. Most Civil War surgeons had never treated a gunshot wound and many had never performed surgery.” That changed during the course of the war, revolutionizing American medicine, writes Emberton: but it didn’t change anything for those who died along the way.