An article featuring the home built by a Civil War Veteran and now used by new members of the CWRT for their business.

Posted on WFMZ.com Feb 19, 2018

Written by CWRT Board Member Frank Whalen

“Have you heard about the exciting things happening in Allentown?” These are the words that Shelby Edwards and James Whitney, a young couple, recall hearing from a friend, words that began their journey to the Lehigh Valley from Seattle.

Deciding they needed to put their business littledrill LLC (“a photography studio that combines conventional design photography and styling for brands and business”) closer to New York, the two artists/entrepreneurs began looking around. Knowing that the costs of living and operating a business in Manhattan and the general New York/New Jersey metropolitan area were out of their price range, but wanting to live in an urban environment, they were first attracted to urban pioneering opportunities in Detroit.

“We had pretty much made up our minds about moving there,” says Edwards, who is the owner and creative director of littledrill LLC, and had been a top stylist manager for Nordstrom in Seattle, “when a friend told us about Allentown.” Not only was it affordable for them but the Lehigh Valley was close enough to New York for them to get in and out of. Both she and Whitney, who is a professional photographer, were excited and acted. Since last year they have purchased a house and a business space in downtown Allentown. As part of what Professor Richard Florida christened “the creative class” that has been reviving American cities, the couple would be considered cutting edge.

But there is another aspect of 1122 Hamilton, one that Edwards and Whitney were not aware of when they brought the property. They have since discovered that the building was built in 1872 by carpenter and wood worker artist Abraham Babp as a home for his family. Although the space has been much changed since Babp’s day, Edwards and Whitney sense a link with the building’s history. “Knowing that a creative person, a wood worker/artist like Babp made his home here adds a whole wonderful dimension to the space for us,” says Whitney. “It is almost as if we in are a part of a continuity with the city’s artists and artisans of the past.”

On October 24, 1929 the New York Stock Exchange collapsed in a frenzy of stock-selling, heralding the arrival of the Great Depression. All of which held no interest for 92-year-old Abraham Babp of 1122 Hamilton Street. Lying in bed in his home, he was dying. For two weeks Babp, who had enjoyed good health for many years, could feel old age and his aliments catching up with him. But almost to the end his mind remained clear. Finally, at 9 o’ clock on the evening of October 25th, 1929, with his unmarried daughter Anna nearby, Babp joined in death his wife Sarah, who had died 15 years before. He was buried next to her in Fairview Cemetery.

By standards of any era Babp had lived a good, long life. And from his birth on June 17, 1837 to Charles and Lydia Shug Babp in Forks Township near Easton, he had seen changes in technology that included the railroad, the telephone and the light bulb. His obituary notes that he particularly observed and commented on the changes of transportation from wagon, to horse drawn street car, to electric trolley car and finally to automobile that passed outside his Hamilton Street front door.

Sometime in his youth Babp left Northampton County for Allentown. Here he went to work for Charles Hanzelman’s organ factory (his obituary misspelled it Heintzleman, apparently confusing it with a prominent Allentown family) to learn the trade of organ maker. The factory was located on Walnut St. near 9th. The term factory in the context of pre-Civil War Lehigh Valley should not be taken to mean mass production. Like many things in the 19th century, organ making was still largely a skilled trade. Babp should be seen as more of a skilled organ maker then a factory worker.

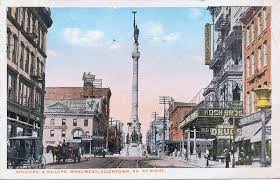

The biggest thing that happened in Babp’s long life was the Civil War. Although there are no known photos of Babp, he may be in one of those collective photos of graying, bewhiskered veterans that were taken in the early 20th century at Center Square. On September 17, 1861 he joined the 51st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He signed up in Northampton County and was a part of Company B, which was largely made up of Northampton County volunteers. The regiment formed up in Harrisburg on November 16, 1861 for three years enlistment. At that time nobody assumed that the war was going to take long. The 24-year-old Babp saw his first action on February 8, 1862 in the battle of Roanoke Island. This was followed by the battle of New Bern, North Carolina.

In July the 51st Pa. was ordered north to Virginia. They saw plenty of action serving at the Second Battle of Bull Run along with the battles of Chantilly and South Mountain. And this put them on September 17, 1862, exactly a year after Babp’s enlistment, in line for the battle of Antietam (Lee’s invasion into Maryland) as part of the Army of the Potomac.

One of the most important moments of this confused, bloody mess christened with the name of a battle occurred at a stone bridge. Then called Rohrbach Bridge, it was used by farmers to take their produce to market. Today it is known as Burnside’s Bridge after the bumbling Union General Ambrose Burnside who had been given the task of capturing it. His commander was the imperious, ambitious General George McClellan, aka the Little Napoleon. McClellan despised Lincoln, who he went out of his way to snub. He knew he would make a better president than that hayseed with his corn-fed jokes and ran against him for the White House in 1864. He lost.

Burnside’s opposite number was Confederate Brigadier General Robert Toombs. Toombs was convinced that by rights he should be the President of the Confederacy. After a brief, tumultuous time as the Secretary of State, he resigned to join the army.

Historians still debate whether Burnside or McClellan was most responsible for sending the flower of the Union Army charging against entrenched Confederate sharpshooters. But send them they did, turning the Antietam Creek red. After three hours of this futile combat the 51st Pennsylvania and the 51st New York were called in to take up the task.

Both regiments were led by Brigadier General Edward Ferrero, a dapper former dancing master from New York who gave a rousing speech.

Finally, the 51st Pa. in the person of Corporal Lewis Patterson spoke up. Described by historian Stephen Sears as a “fractious head case outfit,” they had been denied their whiskey ration for some infraction. “If we take the bridge, sir, can we have our whiskey?” shouted Patterson. Without missing a beat Ferrero shouted back, “Yes, by God!” The words were greeted with a cheer.

The Rebels were low on ammunition and had been fighting for three hours. Yet they still were able to keep up a heavy fire. Members of the bridge assault started to drop. Finally, the two regiments joined and, Sears writes, “in a solid column under two regimental flags side by side,” they carried the bridge. Standing next to the bridge, Col. John F. Hartranft, of the 51st Pa and later to be Pennsylvania’s governor was shouting himself hoarse. “Come on boys, for I can’t halloo anymore.” When his voice finally gave out Hartranft vigorously waved his hat.

A few days after. when one of “the bloodier contests of that bloody day was over,” the dancing master kept his promise and 51st Pa. got its reward, a full keg of it. They had suffered 21 dead and 84 wounded.

Where Private Abraham Babp was in all this is unknown. But one thing is fairly certain, he was not with his comrades when they faced the Rebels again at Fredericksburg in December, 1862 when Burnside was defeated by Lee. It was probably in early October, 1862 when they were camped at Pleasant Valley, Maryland that Babp left them. Babp became ill from with what the newspaper called “unsanitary camp conditions,” i.e., dysentery, which took the lives of more men North and South than bullets and also that of little Willie Lincoln, President Lincoln’s son.

Babp was taken to Harewood military hospital in Washington, to recover. It was here that he discovered his wood working skills. “He showed adeptness at wood carving by whittling from roots dainty napkin rings that are really works of art,” noted his obituary. “Three of these completed in November and December of 1862, encircled with blossoms and twigs, are all part of the main piece of wood. Carved on the edge are his name and regiment with which he served, the name of the hospital and the date when completed. Rings, emblematic of his regiment were also carved by him from bone and wood.”

Babp was discharged from the 51st Pa. on April 17, 1863. He returned to Allentown and took up his work as an organ builder, only now using his skills as a woodworker to decorate them as well. He also installed organs in churches. In 1878/79 Babp began to list himself in the city directory as a carpenter instead of organ maker. Charles Hanzelman closed the organ factory in 1881 and died the following year.

For the next 40 years Babp built many homes in Allentown. He did so working in cooperation with other artesian builders. By the early 20th century he was listed in the city directory as a yeoman, someone who lived off his investments in local property, many of which he probably built than rented out.

Sometime after returning from the war Babp married Sarah R. Kramer. In 1872 he built his home at 1222 where he raised two daughters. His wife died around 1915. He lived on in his home with daughter Anna (his other daughter married and moved to New York) until his death. Anna Babp lived there until her death in the 1940s. Shortly thereafter it was converted to offices.

Shelby Edwards and James Whitney honor and respect Abraham Babp’s life and memory and his spirit. “We feel in a way he is welcoming us to Allentown.”