Standing at the top of the Pinnacle Overlook, I could visualize why both sides of the Civil War considered Cumberland Gap such a strategic outpost. The views from this 2,440-foot high perch are long. On a clear morning over layers of gently rolling hills, I saw the Great Smoky Mountains 100 miles away on the distant horizon. Formerly Confederate Virginia lies to the southeast, and to the southwest formerly Confederate Tennessee. Union-allied Kentucky is situated to the north.

The terrain of this tri-state juncture made the gap a prominent passageway for millennia before and during the war. The overlook sits atop a nearly-100-mile-long ridgeline called Cumberland Mountain, part of the Appalachians that forms a natural and formidable barrier between the two sides. Peering down to the west, I could make out Cumberland Gap, the lowest pass in the region. Originally carved by the Yellow River, this deep notch in the ridge allows easy passage through. Just to the north lies a relatively flat basin, an anomaly in this mountainous terrain. A blanket of morning fog was settled into this ancient meteor crater, drifting along the contours of its dynamic past.

“When the war began, the Confederate strategy in the western theatre hinged on Cumberland Gap,” explained Dr. Lucas Wilder, Civil War history expert and park ranger. “They established it as one of the main bases of operation and hoped to block a Union invasion with a defensive line extending west.”

The Union also valued the gap. A major east-west railroad connecting the Confederacy ran just 40 miles south, and they hoped to sever the supply route. The northern presence also supported a strong pro-Union faction in eastern Tennessee; thousands of young men escaped north to Kentucky from the region to enlist.

While made famous by Daniel Boone as the best way through the mountains, Cumberland Gap is not the only way. Armies from both sides breached the line through some of the multiple gaps through the mountains. And yet, despite its anticipated importance and the fact that Cumberland Gap changed hands several times during the war, no major battles were fought there. The park interprets what it was like to serve here and preserves some notable reminders of the war.

The Confederates controlled the gap starting halfway through 1861. Under the command of General Felix Zollicoffer they built fortifications on the north side of the mountain to protect against a Union invasion. In mid-1862, however, they were ordered to move back deeper into Tennessee. Union forces moved in and built fortifications on the south side of the mountain.

But Northern forces held the gap for only a few months. In September 1862 they left during a major southern invasion into Kentucky and the Confederates moved back in. A year later, Union forces surrounded the southern troops from both sides of the gap. By this point in the war, the north was in control of Knoxville and much of eastern Tennessee. The southern troops were outnumbered and surrendered, knowing no reinforcements were on the way.

Today, short trails from the park road to the overlook lead to two of the 1860s' earthwork fortifications, Fort McCook and Fort Lyon. The area originally held 16 forts, eight built by each side, some which were elaborate enough to fit 10 cannons.

Besides the preserved fortifications, visitors can best experience the lingering presence of war-time troops on a ranger-guided tour of Gap Cave. This five-level, 18-mile cavern provides a peek into the concentration of caves and karst formations in the park as well as a long history of human visitation. Soldiers from both sides stationed at the gap, bored from long days without much action, would venture into the cave.

Park records indicate that more than a thousand soldiers explored the cave in those few years. Their letters home reveal a level of knowledge and awe in detailed accounts of their experiences. Some knew, for example, the names of stalactites and stalagmites and the scientific process of their formation. Others described the beauty of room after room of columns, flowstones, and cave bacon in shades of white, black, and yellow, colored by minerals.

On my cave tour, I imagined having much of the same experiences as these long-ago visitors. We spied a cave salamander perched by the path and ducked as several startled bats flew around our heads. The only light inside the cave was what we carried; flashlights were issued to us upon our arrival for the tour. Then we entered the Civil War room and I felt an even more direct connection.

Here, the soldiers left a piece of themselves behind. More than 300 veterans emblazoned their names in the cave, and the walls of this room are covered with historical graffiti. Most of the names we know little about beyond a mention in the census or an attribution to a military unit. But Dr. Wilder, our guide, pointed out one rather large name, partially hidden behind a column. James Edwards Rains was Confederate commander of the gap for six months. A Nashville native, Rains graduated from Yale Law School and served as district attorney in Tennessee. As a soldier, he reached the rank of brigadier general before being shot through the heart at the Battle of Stone’s River. There is one rather curious aspect of Rains’ signature: his last name was misspelled as “Raines.” Dr. Wilder surmises his men wrote it for him after his visit.

While I was surrounded by soldiers’ names in the Civil War room and imagined their explorations, the place I most closely felt their experience of war was in the cave’s Music Room. Dr. Wilder demonstrated the room’s great acoustics with a song, and the intricate cave structure clarified his clear baritone voice. “Rebel Soldier” is a sad, slow Civil War ballad from southern Appalachia. Written from a Confederate point of view, it tells a universal story of war, of love and homesickness and battle and death. Hearing it in the cave, where so many soldiers had spent part of their war experience, was a haunting and moving reminder of some of the many who traveled Cumberland Gap before me.

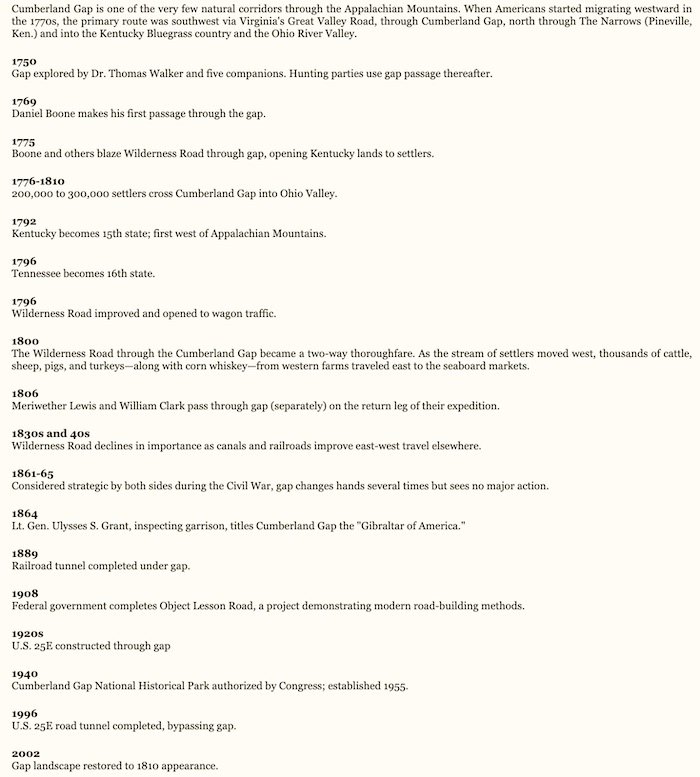

Cumberland Gap National Historic Park interprets thousands of years of human travel, from Cherokee and Shawnee traders to Daniel Boone and his Wilderness Road to early tourists exploring Appalachian Mountain beauty.